REVIEW: Bohren & Der Club of Gore @ Union Chapel

Contributor Josefus Haze caught Bohren & Der Club of Gore at Union Chapel last Friday, where the German doom jazz outfit performed their latest album Patchouli Blue in full. Here’s his take on what went down in one of London’s most distinctive venues.

Earth has many holy places. Natural or manmade, these are sites that inspire awe, spaces that change human perspective in a particular way. Islington’s Union Chapel is one of them.

Tonight, the faithful file in with electric anticipation, for we are to witness a rare event. Not a miracle or second-coming, but a chance to see Bohren & Der Club of Gore perform on our little island.

As well as acoustics and aesthetics, minister Dr Henry Allon and architect James Cubitt designed Union Chapel with a focus on inclusivity, with concentric rows of pews laid out more like a concert hall than your average church. Every congregation member had the right – in the minds of Allon and Cubitt – to an equally good view of the show.

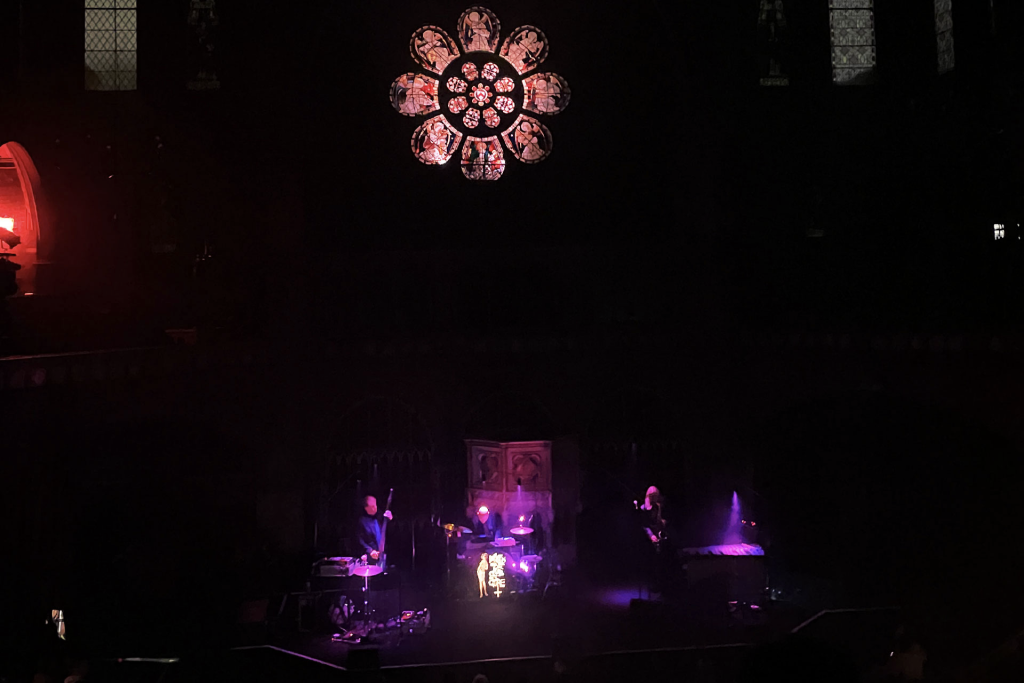

Perhaps they did not intend members to enjoy a double Jameson’s before service, but then I, just as they, am nonconformist in my worship. I take in my spirit and find a pew on the balcony. Main lights go dim, leaving only backlit stained glass, and a stage bathed in red.

A hooded figure enters stage left. At centre stage he turns to bow over a table of electronic instruments, a Byzantine monk before an altar, long beard glinting in what little light there is.

Deep and slow a low bass tone fills the hall like a Gregorian chant. We sit transfixed, silent. Several undulations later, a high tone is introduced, angelic and ethereal as a choir. I gaze at the rose window that meets me at eye level. Its leaded angels shimmer.

As the electric choir’s first swells retreat beneath the bass, we notice subtle changes snuck in by our monastic maestro. Soon the voices return but altered. Kevin Richard Martin continues his hide and seek oscillations with a conductor’s precision, until their final descent into pin-drop silence, the respectful pause between performance and applause you only get from a truly captivated audience.

Intermission passes like communion wine and the congregation returns to the main hall for tonight’s key sermon. Where once red light was all there was, two par cans now bleed slowly through every colour of the stained glass above. Three shadow-drenched figures take the stage. We erupt in applause before they are even positioned at their instruments.

Morten Gass lifts his guitar to pluck the opening notes of Total Falsch. They ascend to the dome above, reflect and descend in a rain of reverb onto Robin Rodenberg’s deep double bass. I am torn. My desire had been to welcome those deep tones into my gut, as before a rig at a rave. Perched upon high where low frequencies fear to tread, I feel something else, some higher resonance in this marriage of mood and music.

I look again at the rose, close my eyes, and as Christoph Clöser begins the first bass sax refrain, bow my head in reverence. I am enveloped.

Our doom jazz overlords have decided to treat the congregation to a complete performance of their 2020 release Patchouli Blue, by far their most emotionally diverse album, at least within the context of the Bohren signature sound. Where their earlier albums tread the gumshoe’s footpath of detective jazz stylings, here they tend more often to lift the listener above the gloom for moments of contemplation.

I had expected a straight-through performance, with no introductions or speaking between the tracks. Clearly Bohren knows better, and I concede that they are right. To maintain such a heavy mood for so long would make for an oppressive experience, and in any case, the Clöser’s wryly grim patter serves as perfect counterpoint to the seriousness of the band’s music.

Sonically, aesthetically, thematically, band and venue are beautifully matched. Churches are designed to invoke reverence, to accentuate the subtleties of sound; we can even hear the breath leave Christoph’s lips before we hear the note. And in those tunes where he switches between sax and vibraphone, the reverb of one instrument blends with the other as though played simultaneously, if only for a moment.

It feels odd to describe such slow music as “tight”, but that it is. These three perform their compositions with astonishing precision. Like father, son, and holy spirit, they are as one, a musical trinity.

Union Chapel’s founder, Dr Allon is said to have held religious music in high regard, investing much effort into the building’s acoustics. With his brainchild still hosting such events as this, even the most hardnosed sceptic must feel that somewhere his spirit smiles still.

by Josefus Haze

Back to home.